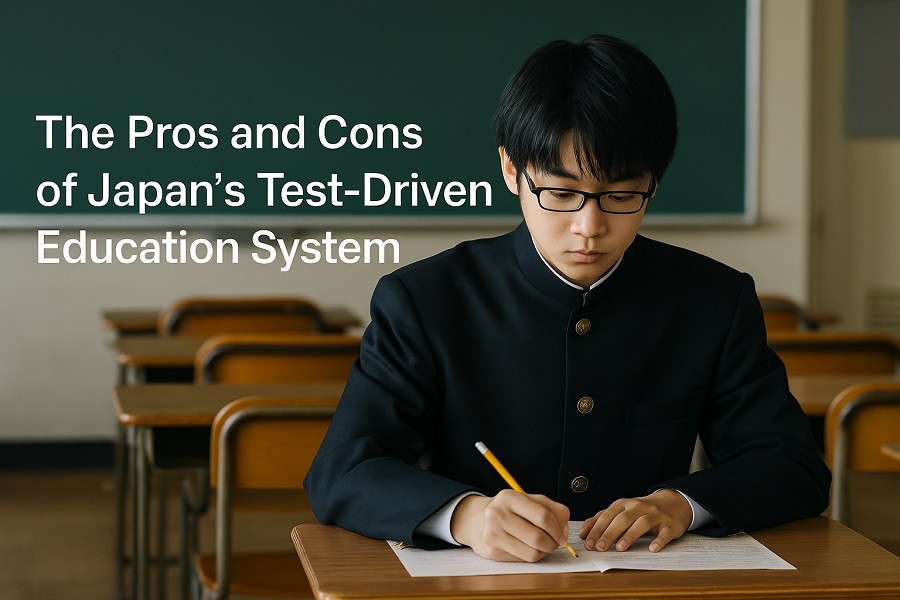

In Japan, a student’s academic path — and sometimes future career — can hinge on a single test. But does this high-pressure system help or hurt in the long run?

🎓 Welcome to the Land of Exams

In Japan, tests aren’t just part of school — they’re the school. From elementary years through high school and even college, a student's academic journey is shaped by a series of crucial entrance exams.

This system, often called “examination hell” (shiken jigoku), has produced generations of hard-working, high-performing students. But it also raises important questions about stress, creativity, and the true purpose of education.

So what exactly are the strengths and weaknesses of Japan’s test-focused system?

✅ The Pros: What Japan Gets Right

1. Strong Foundational Knowledge

Japan consistently ranks high in global academic assessments like PISA, especially in math, science, and reading. Students build solid core skills that serve them well in university and life.

2. Clear Academic Pathways

Entrance exams create clear, merit-based routes to prestigious schools and universities. Students know exactly what is expected and can work toward well-defined goals.

3. Work Ethic and Discipline

Preparing for exams builds focus, time management, and perseverance — traits valued not just in academics, but in the workplace and society at large.

4. Efficient Instruction

With nationwide standardized curriculums and aligned assessments, Japanese schools are remarkably efficient at delivering content and maintaining high academic standards.

❌ The Cons: What Gets Left Behind

1. Extreme Pressure and Mental Health

Students often face intense pressure to succeed on entrance exams — some starting as early as age 10. This stress can lead to anxiety, burnout, and even school refusal (futōkō).

2. Rote Memorization over Deep Thinking

Because exams are often content-heavy, students focus on memorizing facts rather than understanding concepts or solving real-world problems. Critical thinking and creativity can be sidelined.

3. Innovation Gap

While Japan produces capable workers, some argue that the system doesn't foster the kind of original thinking and risk-taking needed for entrepreneurship or scientific breakthroughs.

4. Inequality in Opportunity

Access to cram schools (juku) gives wealthier students an edge, creating gaps in educational equity — even in a country known for relative social equality.

📚 What Do Japanese Students Actually Face?

Let’s break it down:

- Junior high entrance exams: Common in urban areas for elite private schools

- High school entrance exams: Mandatory for public schools; competitive for top schools

- University entrance exams: National Common Test + additional school-specific exams for top institutions like the University of Tokyo or Kyoto University

Failing an exam can mean a student must either attend a less prestigious school or spend an extra year as a "ronin" (a student who studies for re-entry).

🌍 How Does This Compare Internationally?

| Country | Focus | Evaluation Style |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | Academic rigor, test scores | High-stakes entrance exams |

| Finland | Equity, holistic development | Teacher assessments, no national tests before age 16 |

| South Korea | Even more test-driven | “Suneung” exam dominates life |

| United States | GPA, essays, extracurriculars | Standardized tests optional in many colleges |

Japan's system produces impressive averages, but may struggle to nurture outliers, visionaries, or risk-takers.

💡 Is Reform Coming?

In recent years, Japan has begun to rethink its education model, introducing more:

- Project-based learning

- Group discussions

- Cross-disciplinary classes

- English communication skills

But progress is slow, and traditional exam culture remains deeply rooted.

🧠 Final Thoughts

Japan’s test-driven education system delivers results, but at a cost. The question isn't whether exams are bad — it's whether we rely on them too much.

Maybe it’s time to ask:

Are we preparing students for tests — or for life?

✅ Next in this series:

“Does Japan's Cram School Culture Really Boost National Strength?”